Hooke's Law

Hooke’s Law is one of the foundational principles of classical mechanics and elasticity theory, describing the linear relationship between the force applied to an elastic body and the resulting deformation, provided the deformation remains within the elastic limit of the material. Formulated in the 17th century by the English scientist Robert Hooke, the law captures the essential behavior of springs, wires, rods, and a wide class of solid materials when subjected to small stresses. In its simplest and most widely used form, Hooke’s Law states that the restoring force developed in an elastic system is directly proportional to the displacement from its equilibrium position and acts in the opposite direction.

Mathematically, this proportionality reflects the tendency of matter to resist deformation and return to its original configuration once the external force is removed. This property is known as elasticity. The domain of validity of Hooke’s Law is limited to small deformations, where the internal molecular forces respond linearly to external stress. Beyond this regime, materials may exhibit nonlinear elastic behavior, plastic deformation, or fracture, none of which are captured by Hooke’s Law.

In a broader physical context, Hooke’s Law serves as the starting point for understanding vibrational motion, wave propagation in solids, and the mechanical behavior of materials. The concept of a restoring force proportional to displacement underlies simple harmonic motion, a central topic in both classical and quantum physics. Systems obeying Hooke’s Law exhibit oscillatory behavior when displaced from equilibrium, making the law essential for analyzing springs, pendulums (in small-angle approximation), lattice vibrations, and acoustic waves.

From a microscopic viewpoint, Hooke’s Law emerges as an effective description of interatomic forces near equilibrium positions. Atoms in a solid are bound by potential energy functions that, when expanded about the equilibrium separation, contain a quadratic term as the leading contribution. This quadratic approximation leads directly to a linear force–displacement relation. Consequently, Hooke’s Law provides a bridge between macroscopic mechanical behavior and microscopic atomic interactions.

In continuum mechanics, Hooke’s Law is generalized to relate stress and strain through elastic constants such as Young’s modulus, shear modulus, and bulk modulus. These constants characterize the stiffness of materials and depend on their internal structure and bonding. The generalized form of Hooke’s Law plays a crucial role in engineering, materials science, geophysics, and applied physics, where predicting deformation under load is of primary importance.

Thus, Hooke’s Law is not merely an empirical rule for springs but a unifying principle that connects mechanics, material properties, and wave phenomena across multiple scales. Its simplicity, wide applicability, and deep physical significance make it a cornerstone of postgraduate-level physics.

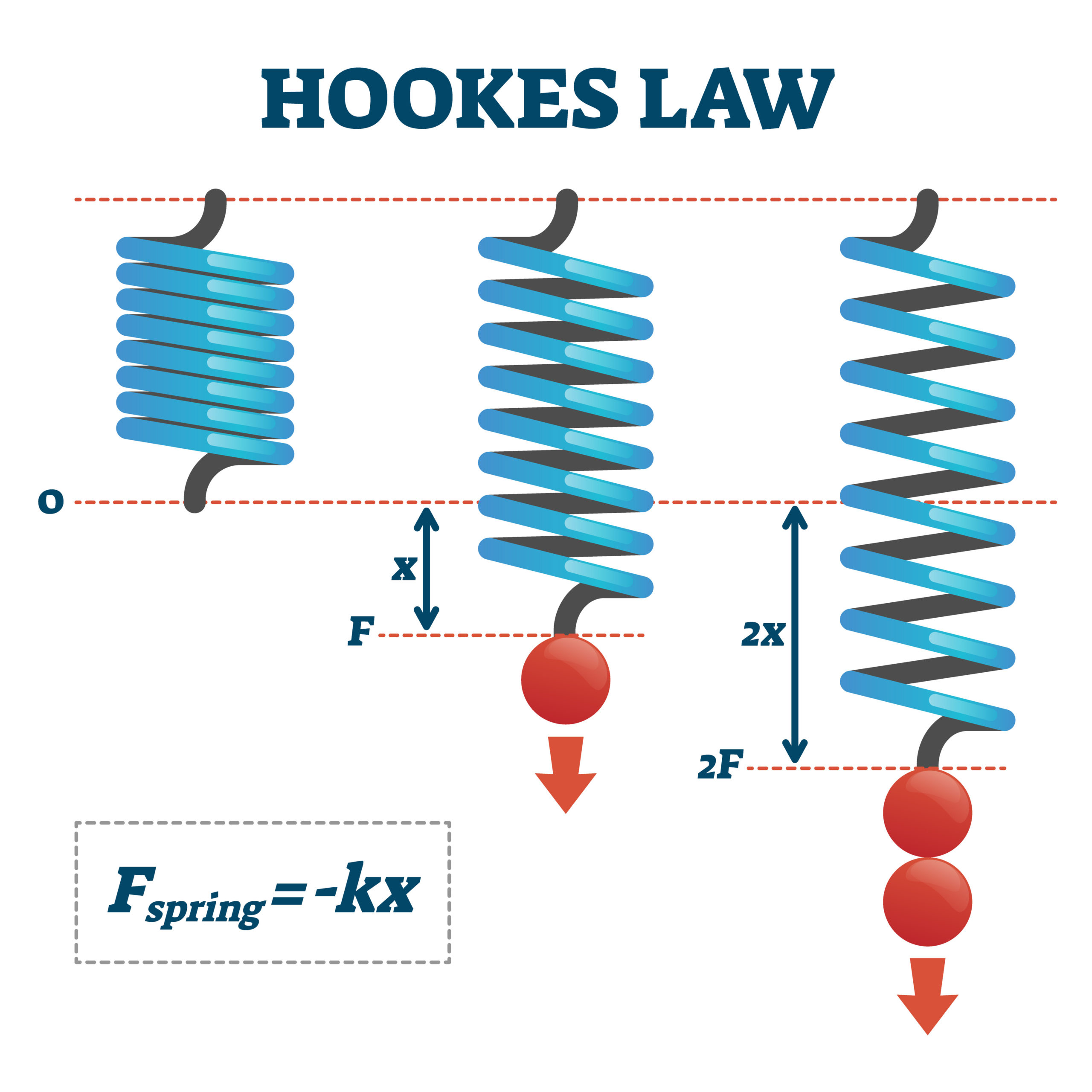

Figure 1: Schematic of a spring anchored to a fixed support and stretched by an applied force, producing an extension $x$.

Consider a one-dimensional elastic system, such as an ideal spring, fixed at one end and free at the other. Let the spring have a natural (unstretched) length $ L_0 $. When an external force is applied, the spring undergoes an extension or compression $ x $, resulting in a new length $ L = L_0 + x $.

The deformation of the spring stores elastic potential energy. For small deformations, the elastic potential energy $ U(x) $ can be expanded as a Taylor series about the equilibrium position $ x = 0 $:

\[U(x) = U(0) + \left( \frac{dU}{dx} \right)_{x=0} x + \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{d^2U}{dx^2} \right)_{x=0} x^2 + \cdots\]At equilibrium, the force is zero, implying

\[\left( \frac{dU}{dx} \right)_{x=0} = 0.\]Choosing the reference such that $ U(0) = 0 $, and neglecting higher-order terms for small $ x $, we obtain

\[U(x) = \frac{1}{2} k x^2,\]where

\[k = \left( \frac{d^2U}{dx^2} \right)_{x=0}\]is a positive constant known as the force constant or spring constant, characterizing the stiffness of the system.

The force associated with this potential energy is given by the negative gradient of the potential:

\[F = -\frac{dU}{dx}.\]Substituting the expression for $ U(x) $, we obtain

\[F = -\frac{d}{dx} \left( \frac{1}{2} k x^2 \right) = -k x.\]This is the mathematical statement of Hooke’s Law. The negative sign indicates that the force is restorative, always acting opposite to the displacement.

In the context of a stretched wire of original length $ L $ and cross-sectional area $ A $, the extension $ \Delta L $ produced by an applied force $ F $ is given by

\[\Delta L = \frac{F L}{A Y},\]where $ Y $ is Young’s modulus of the material. Rearranging,

\[F = \left( \frac{A Y}{L} \right) \Delta L.\]Comparing with $ F = k x $, we identify

\[k = \frac{A Y}{L}.\]Thus, the spring constant is directly related to the material property $ Y $ and the geometry of the system.

Furthermore, substituting Hooke’s Law into Newton’s second law for a mass $ m $ attached to the spring,

\[m \frac{d^2 x}{dt^2} = -k x,\]we obtain the differential equation of simple harmonic motion. Its solution is

\[x(t) = A \cos(\omega t + \phi),\]where the angular frequency is

\[\omega = \sqrt{\frac{k}{m}}.\]This derivation demonstrates how Hooke’s Law leads naturally to oscillatory motion and forms the basis for understanding vibrations in physical systems.

Deductions

- Hooke’s Law is valid only within the elastic limit of a material; beyond this limit, the force–displacement relationship becomes nonlinear.

- The spring constant $ k $ is a measure of stiffness and depends on both material properties and system geometry.

- Hooke’s Law provides the fundamental restoring force responsible for simple harmonic motion.

- The elastic potential energy stored in a deformed body varies quadratically with displacement.

- Generalized Hooke’s Law forms the basis of stress–strain relationships in continuum elasticity theory.