Vector Algebra

Vector Algebra is the mathematical framework that deals with quantities possessing both magnitude and direction and provides systematic rules for their representation, manipulation, and combination, forming the backbone of physical descriptions of space, motion, and fields.

Vector algebra occupies a central position in postgraduate physics because it provides the language in which almost all physical laws are most naturally expressed. The concept of a vector emerged gradually from the study of geometry and mechanics. Early ideas can be traced back to ancient Greek geometry, but the modern formulation began in the 19th century with the work of William Rowan Hamilton, who introduced quaternions, and Hermann Grassmann, whose Ausdehnungslehre laid the foundations of vector spaces and vector operations. Later, Josiah Willard Gibbs and Oliver Heaviside simplified and formalized vector algebra into the dot and cross product notation widely used today. Its importance lies in its ability to encode both magnitude and direction in a compact mathematical form, making it indispensable in classical mechanics, electromagnetism, quantum mechanics, fluid dynamics, and relativity. Physical quantities such as displacement, velocity, acceleration, force, momentum, electric and magnetic fields are inherently vectorial, and vector algebra allows their interactions to be expressed in coordinate-independent form. In contemporary physics, vector algebra underpins tensor calculus and differential geometry, serving as the stepping stone to more advanced mathematical structures. Despite its maturity, current research continues to refine vector-based numerical methods, geometric algebra generalizations, and coordinate-free formulations for complex systems. Recent developments include the use of geometric algebra as a unifying language extending traditional vector algebra, applications in computational physics for efficient simulations, and deeper connections with topology and data-driven physics. Research gaps remain in pedagogy—how vector concepts are best internalized by students—and in extending intuitive vector methods to high-dimensional and non-Euclidean spaces encountered in modern theoretical physics.

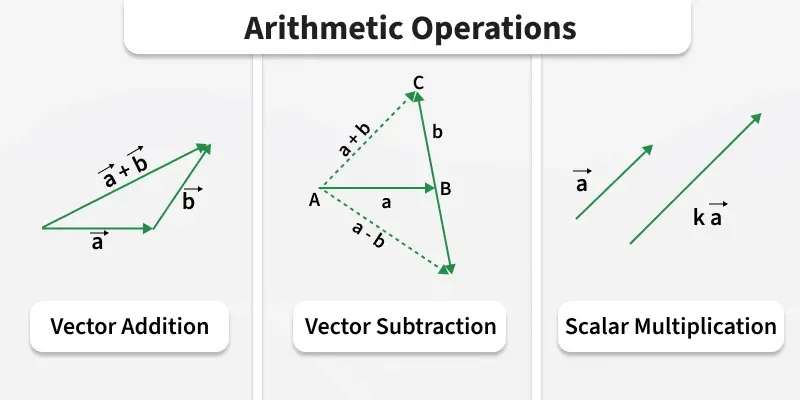

Figure 1: Graphical representation of vector addition, subtraction, and scalar multiplication

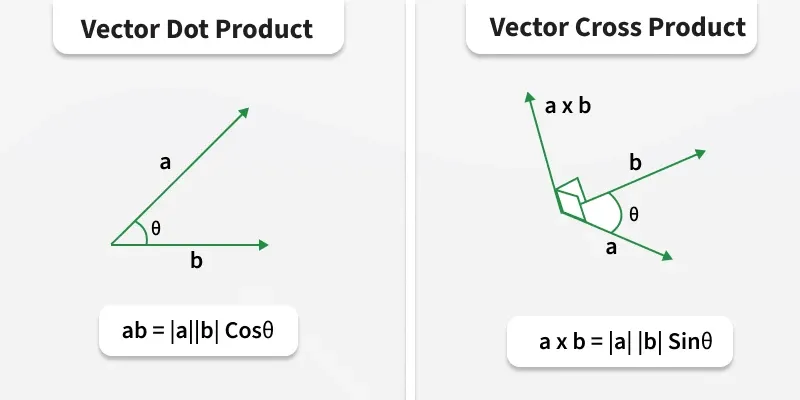

Figure 2: Graphical representation of vector dot and cross products

Mathematical entities and laws used in Vector Algebra

Vector representation:

\(\vec{A} = A_x \hat{i} + A_y \hat{j} + A_z \hat{k}\)Magnitude of a vector:

\(|\vec{A}| = \sqrt{A_x^2 + A_y^2 + A_z^2}\)Scalar (dot) product:

\(\vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} = |\vec{A}| |\vec{B}| \cos \theta\)Vector (cross) product:

\(\vec{A} \times \vec{B} = |\vec{A}| |\vec{B}| \sin \theta \, \hat{n}\)

Consider two vectors in Cartesian form:

\[\vec{A} = A_x \hat{i} + A_y \hat{j} + A_z \hat{k}\] \[\vec{B} = B_x \hat{i} + B_y \hat{j} + B_z \hat{k}\]Derivation of magnitude

The magnitude of $\vec{A}$ is obtained from Euclidean geometry:

\[|\vec{A}|^2 = \vec{A} \cdot \vec{A}\] \[= A_x^2 + A_y^2 + A_z^2\] \[|\vec{A}| = \sqrt{A_x^2 + A_y^2 + A_z^2}\]Derivation of scalar (dot) product

Using component form:

\[\vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} = (A_x \hat{i} + A_y \hat{j} + A_z \hat{k}) \cdot (B_x \hat{i} + B_y \hat{j} + B_z \hat{k})\] \[= A_x B_x + A_y B_y + A_z B_z\]Comparing with geometric definition:

\[\vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} = |\vec{A}| |\vec{B}| \cos \theta\]Derivation of vector (cross) product

The cross product is defined through a determinant:

\[\vec{A} \times \vec{B} = \begin{vmatrix} \hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\ A_x & A_y & A_z \\ B_x & B_y & B_z \end{vmatrix}\] \[= (A_y B_z - A_z B_y)\hat{i} - (A_x B_z - A_z B_x)\hat{j} + (A_x B_y - A_y B_x)\hat{k}\]Its magnitude is:

\[|\vec{A} \times \vec{B}| = |\vec{A}| |\vec{B}| \sin \theta\]Deduction

- Vector algebra provides a coordinate-independent description of physical quantities.

- Scalar products encode projection and energy-related quantities.

- Vector products naturally represent rotational and area-related effects.

- Component and geometric definitions are mathematically equivalent.

- Vector algebra forms the foundation for tensors and advanced physical theories.

Questions

-

Define a vector and give two examples of physical quantities that can be represented as vectors.

-

What is the difference between a scalar and a vector? Provide an example of each.

-

Explain the significance of the dot product in physics. How is it calculated?

-

Describe the cross product of two vectors. What physical quantity does it often represent?

-

How do you determine the magnitude of a vector given its components in three-dimensional space?

-

What is the geometric interpretation of the angle between two vectors? How is it related to the dot product?

-

If two vectors are perpendicular, what is the value of their dot product? Explain why.