Vector Differentiation

Vector differentiation is the mathematical process of determining how vector quantities change with respect to a scalar variable, most commonly time or space, providing a precise language to describe motion, flow, and field variation in physics.

Vector differentiation developed alongside classical mechanics as scientists sought to describe motion in three-dimensional space with increasing precision. Its historical roots can be traced to Isaac Newton, who introduced the concept of fluxions to describe rates of change, and later to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, whose differential notation became the foundation of calculus. As physics evolved, especially during the nineteenth century, the need to differentiate vector quantities such as displacement, velocity, acceleration, and force became unavoidable. The formal structure of vector differentiation was clarified through the works of Josiah Willard Gibbs and Oliver Heaviside, who systematized vector analysis and introduced concise operator-based methods that replaced cumbersome component-wise treatments. The importance of vector differentiation is immense: it forms the basis of kinematics and dynamics, governs the laws of electromagnetism, and underlies fluid mechanics and continuum physics. In modern contexts, vector differentiation is essential in computational physics, numerical simulations, and optimization problems in machine learning–assisted physical modeling. Despite its apparent maturity, research gaps persist, particularly in extending intuitive differentiation rules to curved manifolds and complex coordinate systems encountered in general relativity and modern field theories. Recent developments include the application of differential geometry and tensor calculus to unify vector differentiation in arbitrary coordinate systems, as well as the use of automatic differentiation techniques in large-scale simulations. These advances highlight that vector differentiation remains a living subject, continuously adapting to new theoretical and computational challenges while retaining its foundational role in physics.

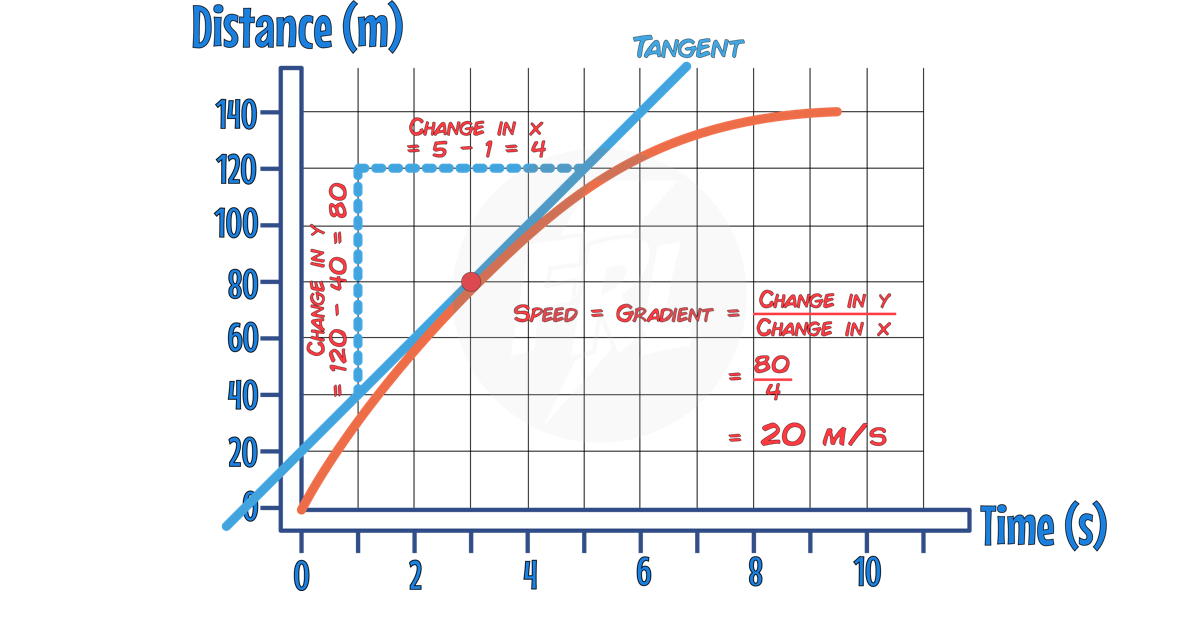

Figure 1: Time variation of position vector leading to velocity and acceleration

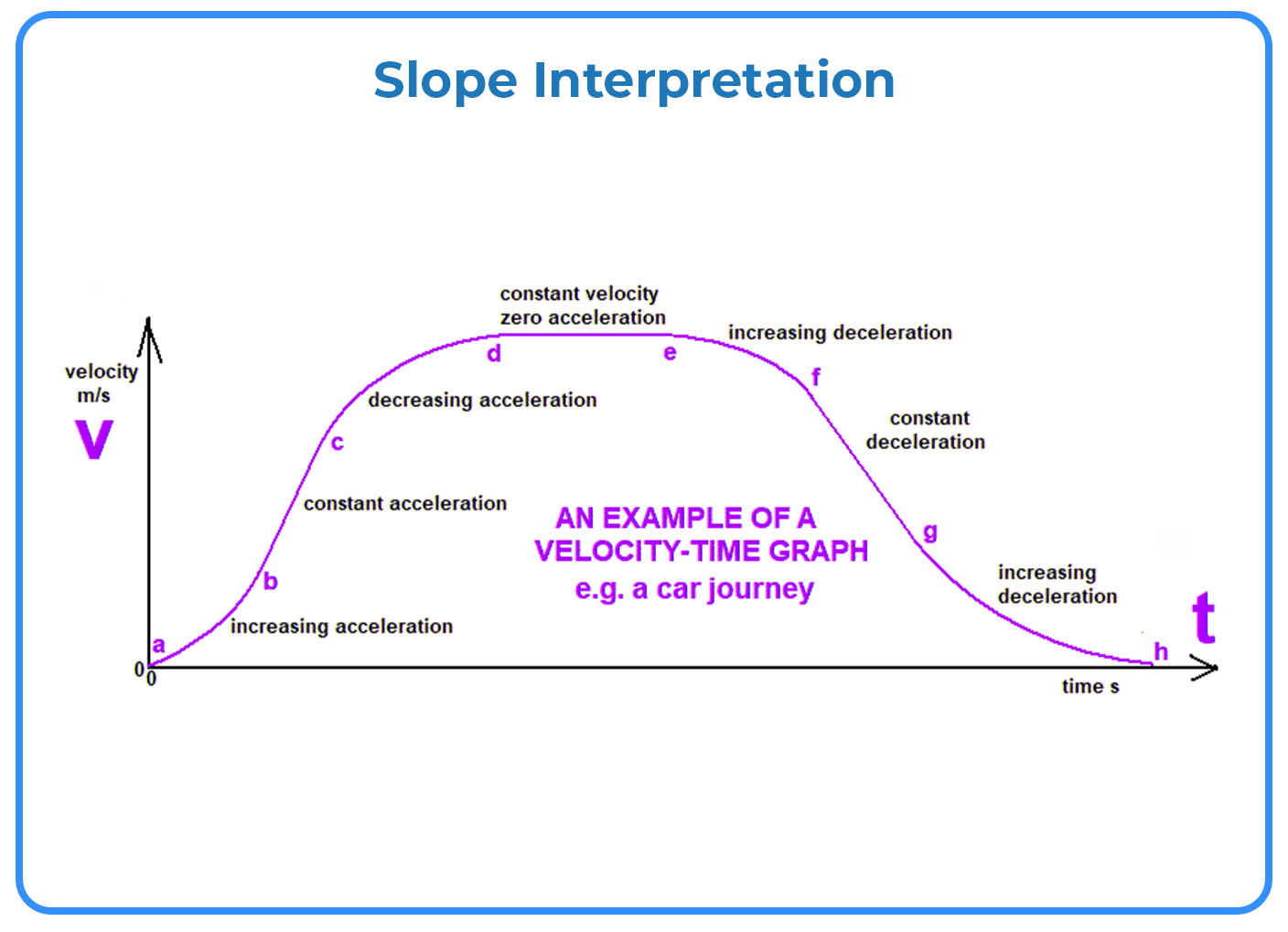

Figure 2: An example of a velocity-time graph for a car journey

Basic Definitions and Notation

\(\vec{r}(t) = x(t)\hat{i} + y(t)\hat{j} + z(t)\hat{k}\)

\(\vec{v} = \frac{d\vec{r}}{dt}\)

\(\vec{a} = \frac{d\vec{v}}{dt} = \frac{d^2\vec{r}}{dt^2}\)

\(\frac{d}{dt}(\vec{A} + \vec{B}) = \frac{d\vec{A}}{dt} + \frac{d\vec{B}}{dt}\)

\(\frac{d}{dt}(f\vec{A}) = \frac{df}{dt}\vec{A} + f\frac{d\vec{A}}{dt}\)

\(\frac{d}{dt}(\vec{A}\cdot\vec{B}) = \frac{d\vec{A}}{dt}\cdot\vec{B} + \vec{A}\cdot\frac{d\vec{B}}{dt}\)

\(\frac{d}{dt}(\vec{A}\times\vec{B}) = \frac{d\vec{A}}{dt}\times\vec{B} + \vec{A}\times\frac{d\vec{B}}{dt}\)

Consider a position vector $\vec{r}(t)$ of a particle in three-dimensional space, expressed as

\[\vec{r}(t) = x(t)\hat{i} + y(t)\hat{j} + z(t)\hat{k}\]Differentiating $\vec{r}(t)$ with respect to time gives the velocity vector,

\[\vec{v} = \frac{d\vec{r}}{dt}\]Since differentiation acts linearly on each component,

\[\vec{v} = \frac{dx}{dt}\hat{i} + \frac{dy}{dt}\hat{j} + \frac{dz}{dt}\hat{k}\]Differentiating the velocity vector once more yields the acceleration vector,

\[\vec{a} = \frac{d\vec{v}}{dt} = \frac{d^2\vec{r}}{dt^2}\]This establishes the fundamental kinematical hierarchy: position, velocity, and acceleration as successive time derivatives.

Vector differentiation obeys rules analogous to scalar calculus. For two time-dependent vectors $\vec{A}(t)$ and $\vec{B}(t)$, the derivative of their sum is

\[\frac{d}{dt}(\vec{A} + \vec{B}) = \frac{d\vec{A}}{dt} + \frac{d\vec{B}}{dt}\]If a vector $\vec{A}(t)$ is multiplied by a scalar function $f(t)$, the product rule applies,

\[\frac{d}{dt}(f\vec{A}) = \frac{df}{dt}\vec{A} + f\frac{d\vec{A}}{dt}\]For the scalar (dot) product of two vectors,

\[\frac{d}{dt}(\vec{A}\cdot\vec{B})\]we apply the product rule component-wise to obtain

\[\frac{d}{dt}(\vec{A}\cdot\vec{B}) = \frac{d\vec{A}}{dt}\cdot\vec{B} + \vec{A}\cdot\frac{d\vec{B}}{dt}\]Similarly, for the vector (cross) product,

\[\frac{d}{dt}(\vec{A}\times\vec{B})\]the derivative distributes as

\[\frac{d}{dt}(\vec{A}\times\vec{B}) = \frac{d\vec{A}}{dt}\times\vec{B} + \vec{A}\times\frac{d\vec{B}}{dt}\]These results are central in mechanics and electrodynamics. For example, differentiating angular momentum $\vec{L} = \vec{r}\times\vec{p}$ with respect to time directly leads to torque, illustrating how vector differentiation connects mathematical structure to physical law.

Deduction

- Vector differentiation generalizes scalar differentiation to multidimensional quantities.

- Velocity and acceleration arise naturally as time derivatives of position.

- Linear, product, dot, and cross product rules preserve vector structure.

- Physical laws often emerge directly from differentiated vector relations.

- Advanced theories extend vector differentiation using geometry and tensors.