Scalar and Vector Products

Scalar (dot) and vector (cross) products are fundamental binary operations between vectors that yield, respectively, a scalar measuring directional alignment and a vector representing oriented area and rotational tendency, forming the mathematical backbone of geometry, mechanics, and field theory.

Scalar and vector products occupy a central place in classical and modern physics because they encode how vectors interact geometrically and physically. The conceptual roots of these products trace back to analytic geometry and vector algebra in the nineteenth century, particularly through the work of William Rowan Hamilton, who introduced quaternions, and Josiah Willard Gibbs and Oliver Heaviside, who independently streamlined vector analysis into the form widely used today. The scalar product emerged naturally from Euclidean geometry as a measure of projection and work, while the vector product arose from the need to describe rotational effects such as torque and angular momentum. Their importance is profound: the scalar product underpins definitions of work, energy, power, and orthogonality, whereas the vector product governs rotational dynamics, magnetic forces, and circulation. In contemporary physics, these products are indispensable in electrodynamics, quantum mechanics, continuum mechanics, and relativistic field theories. Despite their classical appearance, research gaps remain in extending intuitive geometric interpretations to higher dimensions and non-Euclidean manifolds, where generalizations such as exterior algebra and geometric algebra are actively studied. Recent developments include the unification of dot and cross products within geometric algebra, offering compact formulations of Maxwell’s equations and modern computational advantages, and renewed interest in vector operations in data-driven physics and machine learning–assisted simulations, where inner products define similarity measures and optimization landscapes. Thus, scalar and vector products are not merely mathematical tools but evolving concepts that continue to shape theoretical understanding and computational practice.

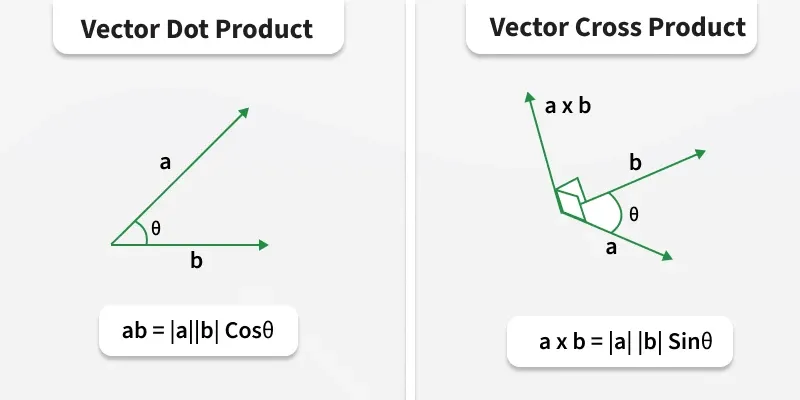

Figure 1: Graphical representation of vector dot and cross products

Key formulas for Scalar and Vector Products

\(\vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} = |A||B| \cos\theta\)

\(\vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} = A_x B_x + A_y B_y + A_z B_z\)

\(\vec{A} \times \vec{B} = |A||B| \sin\theta \, \hat{n}\)

\(\vec{A} \times \vec{B} = \begin{vmatrix} \hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\ A_x & A_y & A_z \\ B_x & B_y & B_z \end{vmatrix}\)

\(W = \vec{F} \cdot \vec{s}\)

\(\vec{\tau} = \vec{r} \times \vec{F}\)

Let two vectors $\vec{A}$ and $\vec{B}$ make an angle $\theta$ between them. Consider resolving $\vec{B}$ into components parallel and perpendicular to $\vec{A}$. The component of $\vec{B}$ along $\vec{A}$ is $B \cos\theta$. The scalar product is defined as the product of the magnitude of one vector and the projection of the other along it, giving

\[\vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} = A (B \cos\theta)\]or equivalently

\[\vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} = AB \cos\theta\]This immediately shows that the scalar product measures directional similarity: it is maximum when vectors are parallel and zero when they are perpendicular. In Cartesian coordinates, let

\[\vec{A} = A_x \hat{i} + A_y \hat{j} + A_z \hat{k}, \quad \vec{B} = B_x \hat{i} + B_y \hat{j} + B_z \hat{k}\]Using orthonormality of unit vectors, $\hat{i}\cdot\hat{i}=1$ and $\hat{i}\cdot\hat{j}=0$, we obtain

\[\vec{A} \cdot \vec{B} = A_x B_x + A_y B_y + A_z B_z\]For the vector product, consider the parallelogram formed by $\vec{A}$ and $\vec{B}$. Its area is $AB \sin\theta$. The vector product is defined as a vector of this magnitude, perpendicular to the plane of $\vec{A}$ and $\vec{B}$, with direction given by the right-hand rule:

\[\vec{A} \times \vec{B} = AB \sin\theta \, \hat{n}\]where $\hat{n}$ is the unit normal. Expressing this in component form yields the determinant representation,

\[\vec{A} \times \vec{B} = \begin{vmatrix} \hat{i} & \hat{j} & \hat{k} \\ A_x & A_y & A_z \\ B_x & B_y & B_z \end{vmatrix}\]Expanding the determinant step by step,

\[\vec{A} \times \vec{B} = \hat{i}(A_y B_z - A_z B_y) - \hat{j}(A_x B_z - A_z B_x) + \hat{k}(A_x B_y - A_y B_x)\]Physical interpretations follow directly. Work done by a force $\vec{F}$ through displacement $\vec{s}$ is

\[W = \vec{F} \cdot \vec{s}\]indicating that only the component of force along displacement contributes to work. Similarly, torque is defined as

\[\vec{\tau} = \vec{r} \times \vec{F}\]showing that rotational effect depends on the perpendicular component of force relative to the lever arm.

Deduction

- Scalar product quantifies projection and energy-related effects.

- Vector product encodes oriented area and rotational influence.

- Orthogonality and parallelism are naturally characterized by these products.

- Classical mechanics and electromagnetism rely fundamentally on them.

- Modern generalizations extend these ideas beyond three-dimensional space.