Franck Condon Principle

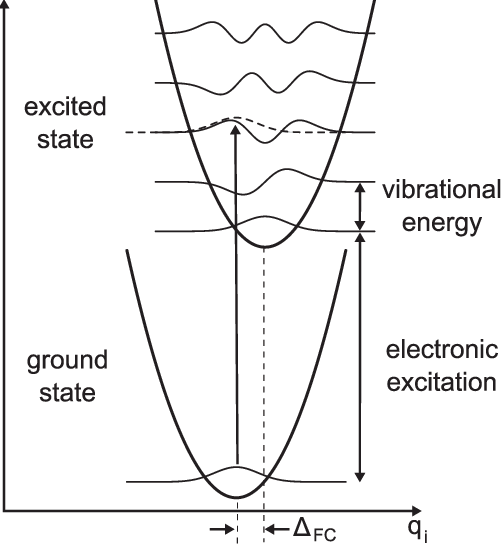

The Franck–Condon principle is one of the most fundamental concepts in molecular spectroscopy, explaining why vibrational structures appear in electronic spectra of molecules and why certain transitions are more intense than others. When a molecule undergoes an electronic transition—whether by absorption or emission of radiation—the change in the electronic state occurs on a timescale much faster than nuclear motion. Electrons are extremely light compared to nuclei; therefore, their transitions happen almost instantaneously relative to the vibrational and rotational movement of the nuclei. As a consequence of this difference in timescales, the nuclei can be considered “frozen” during the electronic transition. This approximation is the core of the Franck–Condon principle and leads to a vertical transition between potential energy curves on a Born–Oppenheimer energy diagram.

Because nuclei cannot adjust their positions during the electronic excitation, the most probable transition occurs between vibrational states whose wavefunctions have the greatest spatial overlap at the fixed internuclear distance of the initial vibrational state. This overlap determines the intensity of each vibrational band and gives rise to characteristic progressions in electronic spectra. The greater the overlap between the vibrational wavefunctions of the initial and final electronic states, the stronger the observed spectral line. These overlaps are quantified mathematically as Franck–Condon factors, which play a central role in determining selection rules and intensity distributions.

The principle is best visualized by plotting the potential energy curves of the ground and excited electronic states. If the equilibrium internuclear distances of both states are identical, the strongest transitions occur between identical vibrational quantum numbers ($ v’ = v’’ $). However, if the equilibrium bond length changes upon excitation—a common occurrence—the overlap shifts to higher vibrational levels in the final state. This produces a vibrational progression, often seen as a series of peaks of varying intensities in absorption or emission spectra. The spacing between these peaks gives direct information about the vibrational constants of both electronic states and the geometry of the molecule in its excited state.

The Franck–Condon principle also explains why some transitions are forbidden or weak. Even when dipole selection rules permit a transition, it may still be negligible if the vibrational overlap is small. This interplay between electronic and vibrational wavefunctions makes the principle extremely important for interpreting molecular spectra in gases, plasmas, interstellar media, and many chemical environments.

In addition to its role in spectroscopy, the principle has wide implications in photochemistry, fluorescence, phosphorescence phenomena, and non-radiative transitions. The relative intensities of absorption and emission spectra (such as in fluorescence) often display mirror-image patterns because they arise from similar Franck–Condon considerations. Furthermore, the principle helps explain Stokes shifts, predissociation, and the shape of spectral envelopes in polyatomic molecules.

Mathematical Derivation

Consider a diatomic molecule under the Born–Oppenheimer approximation, where the total molecular wavefunction is separable into electronic and nuclear parts:

\[\Psi(r,R) = \psi_e(r;R)\, \chi_v(R),\]where $ r $ represents electronic coordinates and $ R $ the internuclear separation.

The transition moment integral for an electronic-vibrational transition is:

\[M_{v'v''} = \int \Psi_{v'}^{(f)*}(r,R)\, \hat{\mu}\, \Psi_{v''}^{(i)}(r,R)\, dr\, dR.\]Separating electronic and nuclear components:

\[M_{v'v''} = \left( \int \psi_e^{(f)*}(r;R)\, \hat{\mu}\, \psi_e^{(i)}(r;R)\, dr \right) \left( \int \chi_{v'}^{(f)*}(R)\, \chi_{v''}^{(i)}(R)\, dR \right).\]Define the electronic integral as:

\[\mu_{fi}(R) = \int \psi_e^{(f)*}(r;R)\, \hat{\mu}\, \psi_e^{(i)}(r;R)\, dr.\]Assuming $ \mu_{fi}(R) \approx \text{constant} $ over the region where vibrational overlap is significant, we obtain:

\[M_{v'v''} \propto \int \chi_{v'}^{(f)*}(R)\, \chi_{v''}^{(i)}(R) \, dR.\]The transition intensity is proportional to the square of the matrix element:

\[I_{v'v''} \propto |M_{v'v''}|^2 \propto \left| \int \chi_{v'}^{(f)*}(R)\, \chi_{v''}^{(i)}(R)\, dR \right|^2.\]Define the Franck–Condon factor:

\[q_{v'v''} = \left| \langle \chi_{v'}^{(f)} | \chi_{v''}^{(i)} \rangle \right|^2.\]Thus,

\[I_{v'v''} \propto q_{v'v''}.\]For applications see this link

Deductions

-

The intensity of a vibronic transition depends primarily on vibrational overlap, not only on electronic selection rules.

-

A shift in equilibrium internuclear distance between electronic states generates a vibrational progression, with its maximum determined by the Franck–Condon factor.

-

Electronic transitions are effectively vertical on a potential diagram because nuclear motion is negligible on the electronic timescale.

-

The shape of absorption and emission spectra, including mirror symmetry and Stokes shift, follows directly from Franck–Condon considerations.

-

Franck–Condon factors provide a powerful spectroscopic method to extract equilibrium geometries, molecular constants, and changes in bond lengths between electronic states.