Particle Physics: Particle Classification

Japanese physicist Hideki Yukawa proposed in 1935 that the nuclear force is mediated by a new particle, a meson, whose exchange between nucleons causes the force. He predicted its mass to be about 200 times that of an electron, earning him a Nobel Prize in 1949. Because the new particle would have a mass between that of the electron and that of the proton, it was called a meson (from the Greek meso, “middle”)

- Note: (Yukawa’s predicted particle is not the gluon as previously mentioned, which is massless and is today considered to be the field particle for the nuclear force.)

In modern physics, particle interactions are explained through the exchange of field particles (or gauge bosons). These particles are emitted and absorbed by interacting particles, creating forces. The electromagnetic force is mediated by photons, the nuclear force by gluons, the weak force by W and Z bosons, and the gravitational force by gravitons. The interactions, their ranges, and relative strengths are summarized in the table below.

| Interaction | Relative Strength | Range of Force | Mediating Particle | Mass of Field Particle (GeV/c²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear | 1 | Short (< 1 fm) | Gluon | 0 |

| Electromagnetic | $10^{-2}$ | Infinite | Photon | 0 |

| Weak | $10^{-5}$ | Short (< $10^{-3}$ fm) | W⁺, W⁻, Z⁰ bosons | 80.4, 80.4, 91.2 |

| Gravitational | $10^{-39}$ | Infinite | Graviton | 0 |

In efforts to substantiate Yukawa’s predictions, physicists began experimental searches for the meson. In 1937, Carl Anderson discovered a particle approximately 207 times the mass of electron, initially thought to be Yukawa’s meson. However, it interacted weakly with matter and was later identified as a muon, participating in weak and electromagnetic interactions. Yukawa’s prediction was validated in 1947 with the discovery of the pi meson (pion), which exists in three charge states: $\pi^+$, $\pi^-$, and $\pi^0$, with masses around $140 \, \text{MeV}/c^2$. Two muons exist $\mu^+$ and its antiparticle $\mu^-$. Both pions and muons are highly unstable and decay into lighter particles. For example, The $\pi^-$, which has a mean lifetime of $2.6 \times 10^{-8} \, \text{s}$, decays to a muon and an antineutrino:

$\pi^- \to \mu^- + \bar{\nu}$

The muon, with a mean lifetime of $2.2 \, \mu\text{s}$, subsequently decays into an electron, a neutrino, and an antineutrino:

$\mu^- \to e^- + \nu + \bar{\nu}$

Particle Classification

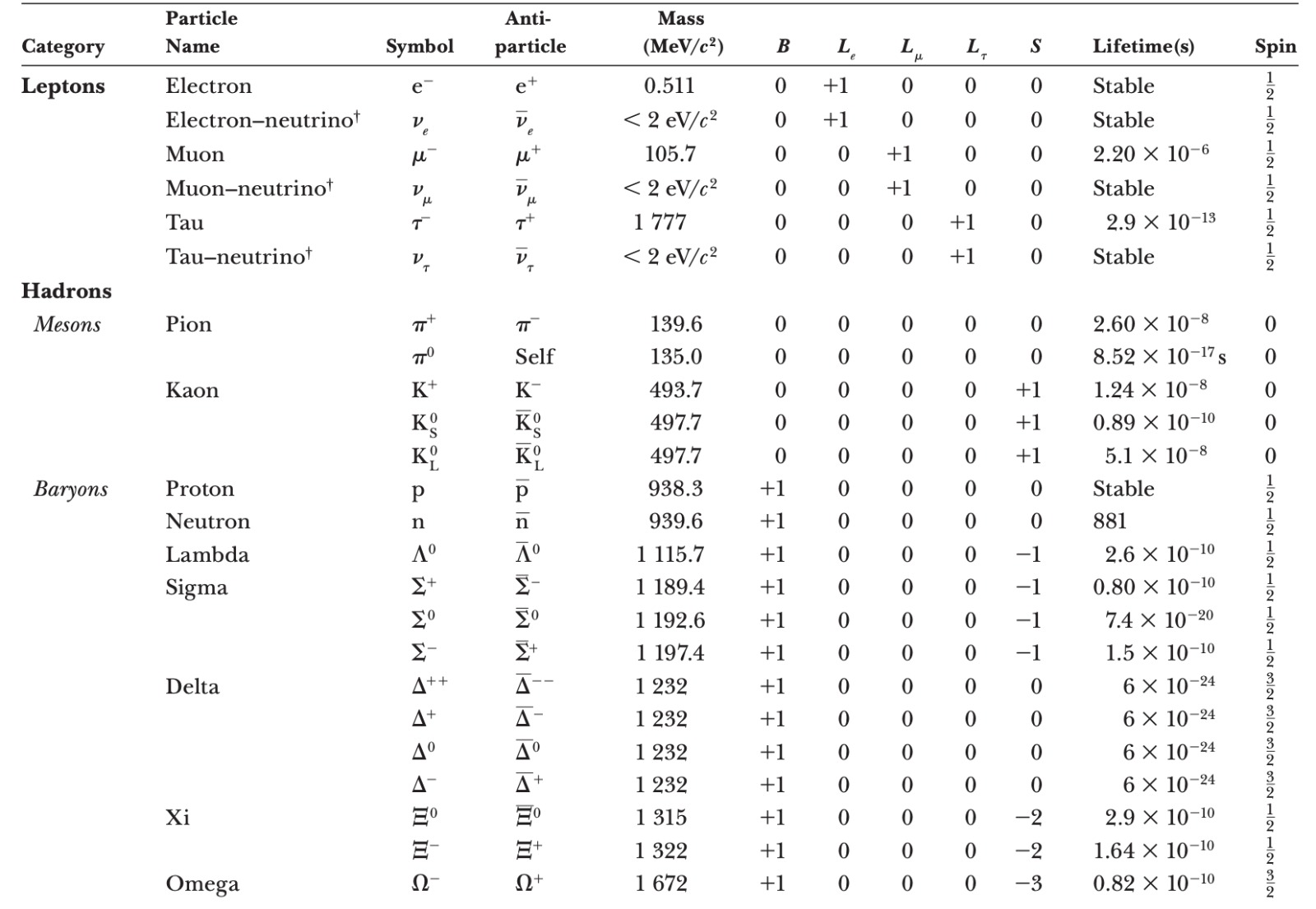

We’ve learned about pions and muons. We have a growing list of particles(more than 300). Apart from field particles, all particles fall into two main groups: hadrons and leptons.

Hadrons

Particles that interact through the strong force (as well as through the other fundamental forces) are called hadrons. The two classes of hadrons, mesons and baryons, are distinguished by their masses and spins.

- Mesons have zero or integer spin (0 or 1). Yukawa proposed their mass to lie between that of the electron and proton. While several mesons fall in this range, others with greater mass than the proton have also been discovered. Mesons eventually decay into electrons, positrons, neutrinos, and photons. The pions are the lightest known mesons.

- Baryons, the second class of hadrons, have masses equal to or greater than the proton mass, and their spin is always a half-integer value (1/2, 3/2, …). Protons and neutrons are examples of baryons, as are many others. Except for the proton, all baryons decay to produce a proton.

It is now believed that hadrons are not elementary particles but are made up of more fundamental units called quarks.

Leptons

Leptons (from the Greek leptos, meaning “small” or “light”) are particles that do not interact via the strong force. All leptons have spin 1/2. Unlike hadrons, which have size and structure, leptons are considered truly elementary, meaning they have no internal structure and are point-like.

The table below lists the known leptons and Hadrons along with their properties.