Particle Physics: Quarks

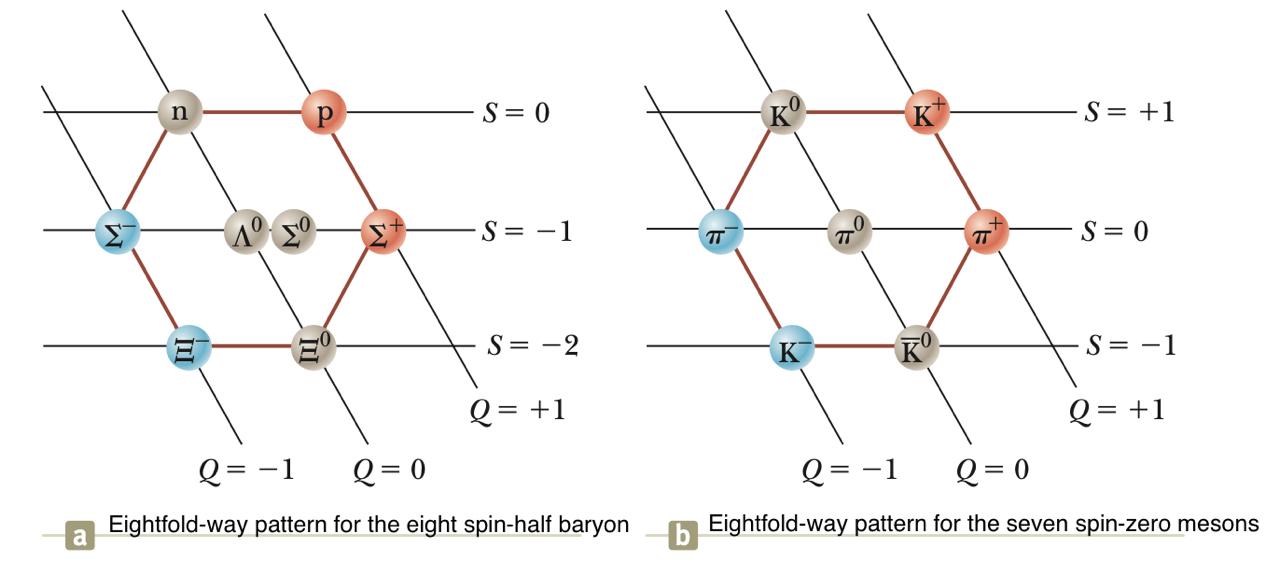

Scientists use patterns in data to understand natural phenomena, such as differences in the specific heat of gases, ionization energy levels, and nuclear binding energy. One of the most significant examples is the periodic table, which explains the behavior of over 100 elements formed from just protons, neutrons, and electrons. Inspired by the periodic table, physicists have sought patterns to classify the hundreds of observed particles. Baryons with spin $\frac{1}{2}$ and spin-zero mesons, for instance, can be grouped based on properties like strangeness $\mathbf{S}$ and charge $\mathbf{Q}$. The Eightfold Way (Gell-Mann named the patterns the Eightfold Way after the Eightfold Path to nirvana in Buddhism), developed by Murray Gell-Mann and Yuval Ne’eman in 1961, is one such classification scheme.

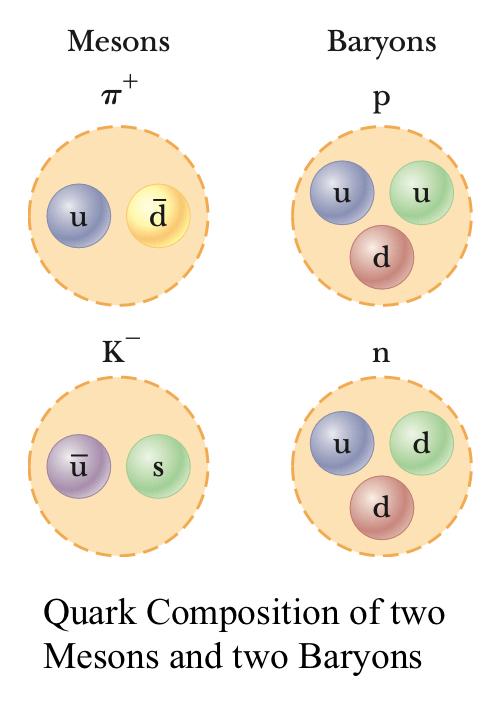

The figure at the top shows the Eightfold Way classification for baryons on the left and mesons on the right. Is it possible that a small number of entities exist from which all these particles can be built?. The existence of the strangeness–charge patterns of the eightfold way suggests that hadrons have substructure. Furthermore, hundreds of types of hadrons exist and many decay into other hadrons. In 1963, Gell-Mann and George Zweig independently proposed a model for the substructure of hadrons. According to their model, all hadrons are composed of two or three elementary constituents called quarks. The model has three types of quarks, designated by the symbols $u$, $d$, and $s$, that are given the arbitrary names up, down, and strange. The figure below shows the quark compositions for mesons and baryons. The various types of quarks are called flavors.

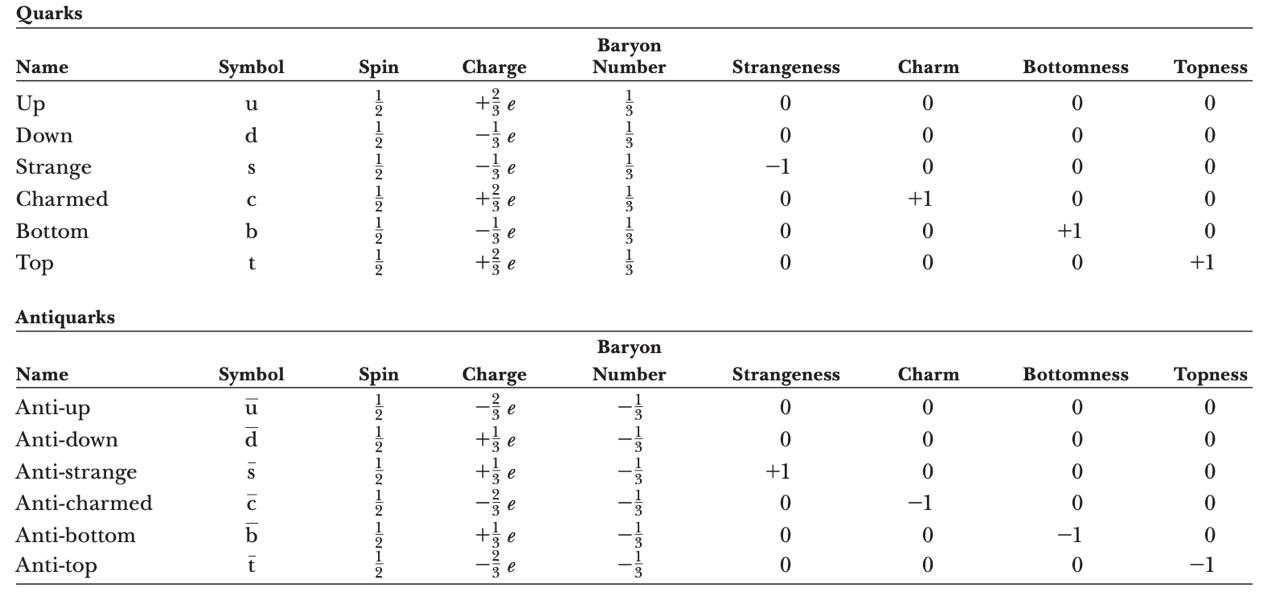

An unusual property of quarks is that they carry a fractional electric charge. The $u$, $d$, and $s$ quarks have charges of $\frac{2}{3}e$, $-\frac{1}{3}e$, and $-\frac{1}{3}e$, respectively, where $e$ is the elementary charge $1.602 × 10^{-19}\; C$. These and other properties of quarks and antiquarks are given in Table below.

The compositions of all hadrons known when Gell-Mann and Zweig presented their model can be completely specified by three simple rules:

- A meson consists of one quark and one antiquark, giving it a baryon number of 0, as required.

- A baryon consists of three quarks.

- An antibaryon consists of three antiquarks.

Charm, Bottom, and Top Quarks

The original quark model, which included the up, down, and strange quarks, encountered limitations when explaining certain experimental decay rates and particle properties. This led to the proposal of a fourth quark flavor, charm ($c$), in 1967. The charmed quark, like the up quark, carries a charge of $+\frac{2}{3}e$ but is distinguished by a quantum number called charm $C$, with the charmed quark having $C = +1$ and its antiquark having $C = -1$. Experimental evidence for the charm quark emerged in 1974 with the discovery of the $\psi$ meson ($c\bar{c}$), a particle significantly more massive and longer-lived than other mesons, leading to the Nobel Prize for Burton Richter and Samuel Ting in 1976.

In 1977, the discovery of a new heavy meson, the upsilon ($\Upsilon$), at Fermilab confirmed the existence of the bottom ($b$) quark. The bottom quark has a charge of $-\frac{1}{3}e$ and is associated with the quantum number bottomness, analogous to charm. Finally, the top ($t$) quark, the heaviest of all quarks with a mass of approximately $173 \ \text{GeV}/c^2$, was discovered in 1995 at Fermilab. The top quark also carries a charge of $+\frac{2}{3}e$. Together with their antiquarks, these flavors complete the six-quark model.

These quarks interact via the strong force, mediated by gluons, and are never observed in isolation due to confinement. Instead, they combine to form mesons (quark-antiquark pairs) and baryons (three-quark combinations). Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) describes their interactions, with color charge playing a crucial role in ensuring the stability and properties of hadrons.

Note: Quarks have never been observed in isolation due to their confinement by the strong force, which increases with distance, similar to a stretched spring. Efforts to create a quark–gluon plasma, where quarks are liberated from protons and neutrons, have shown progress. In 2000, CERN reported evidence of such a plasma from lead nucleus collisions.