Nuclear Reactions

Nuclear reactions can occur when a target nucleus $X$ is bombarded by a particle $a$, resulting in a daughter nucleus $Y$ and an outgoing particle $b$:

\[a + X \rightarrow Y + b\]The reaction energy $Q$ in a nuclear reaction represents the difference between the initial and final rest energies of the participating nuclei. Mathematically, it is given by:

\[Q = (M_a + M_X - M_b - M_Y)c^2\]where $M_a$ and $M_X$ are the masses of the reactants, $M_b$ and $M_Y$ are the masses of the products, and $c$ is the speed of light.

A positive $Q$-value indicates an exothermic reaction, where energy is released. For example, in the reaction:

\(\ce{^1_1H + ^7_3Li -> ^4_2He + ^4_2He}\) ,

the $Q$-value is $Q = 17.3 \, \mathrm{MeV}$. Such reactions often release energy in the form of kinetic energy of the products, making them energetically favorable.

Conversely, a negative $Q$-value corresponds to an endothermic reaction, where energy must be supplied for the reaction to occur. For an endothermic reaction, the bombarding particle must have kinetic energy greater than the magnitude of $Q$. This minimum energy required to initiate the reaction is known as the threshold energy, and it ensures conservation of momentum and energy in the isolated system.

Problem 1: Q Value Calculation for Alpha Decay of $^{226}\text{Ra}$

The $^{226}\text{Ra}$ nucleus undergoes alpha decay according to

\[_{88}^{226}\text{Ra} \rightarrow _{86}^{222}\text{Rn} + _2^4\text{He}\]Calculate the Q value for this process using the formula $Q = \left( M_{\text{initial}} - M_{\text{final}} \right)\times 931.494 MeV/u$. The masses are:

- $226.025408 \, \text{u}$ for $_{88}^{226}\text{Ra}$

- $222.017576 \, \text{u}$ for $_{86}^{222}\text{Rn}$

- $4.002603 \, \text{u}$ for $_2^4\text{He}$.

Problem 2: Energy Released by Fission of 1.00 kg of $^{235}\text{U}$

Calculate the energy released when 1.00 kg of $^{235}\text{U}$ undergoes fission, given that the disintegration energy per event is $Q = 208 \, \text{MeV}$.

Answer: $5.33\times10^{26}MeV$

How much is this energy? The energy released in the fission of 1 kg of $^{235}\text{U}$, if released slowly, is enough to keep a 100-W lightbulb operating for 30,000 years! If the available fission energy in 1 kg of $^{235}\text{U}$ were suddenly released, it would be equivalent to detonating about 20,000 tons of TNT.

Problem 3: Identifying Unknown Nuclides and Particles

Identify the unknown nuclides and particles $X$ and $X’$ in the following nuclear reactions:

(a) $X + _2^4\text{He} \rightarrow _{12}^{24}\text{Mg} + _0^1\text{n}$

(b) $ _{92}^{235}\text{U} + _0^1\text{n} \rightarrow _{38}^{90}\text{Sr} + X + 2( _0^1\text{n})$

(c) $2( _1^1\text{H}) \rightarrow _1^2\text{H} + X + X’$

Classifications of Nuclear Reactions: Blatt, Weisskopf, and Krane

Here we discuss Kenneth Blatt, Weisskopf, and Krane classification which is more specific approach compared to the broader categories of decay and transmutation based on reaction outcomes.

A typical nuclear reaction is represented as:

\[a + X \rightarrow Y + b\]- a: Accelerated projectile.

- X: Target (usually stationary).

- Y and b: Reaction products, where Y is typically a heavy particle and b is a light particle that can be detected.

Types of Reactions

- Scattering Reactions

- Occur when incident and outgoing particles are the same.

- Elastic scattering: When Y and b are in their ground states. The nucleus does not react to this collision in any way. The video below shows an example of elastic scattering.

- Inelastic scattering: When Y or b is in an excited state and decays by emitting gamma rays. After collision with a nucleus, the neutron might transfer part of its kinetic energy. The neutron is slowed down, the nucleus is excited by this excess energy and must release it by the emission of a photon or possibly by another change. If the amount of transferred energy is large enough, the nucleus might disintegrate. The video below shows an example of inelastic scattering.

- Radiative Capture

- If b is a gamma ray, in which case the reaction is called radiative capture.

- During radiative capture, an incident neutron enters the target nucleus forming a compound nucleus and at the same time transferring all its energy to the nucleus. The nucleus is excited by this additional energy and must release it by emitting a photon, or possibly by another type of change. The video below shows an example of radiative capture.

- Nuclear Photoeffect

- If a is a gamma ray, the reaction is called nuclear photoeffect.

- Direct Reactions

- Only a few nucleons participate, with others remaining as passive spectators. Direct reactions happen on the surface rather than in the volume of interacting nuclei.

- Projectile and target are within the range of nuclear forces for the very short time allowing for an interaction of a single nucleon only. These type of reactions are called the direct reactions.

- Direct reactions are well described as a one-step transition from the initial state in the entrance to the final state in the exit channel.

- Direct reactions include: stripping, pick-up, and knockout reactions.

- Compound Nucleus Reaction

- Involves a brief merging of incoming and target nuclei, leading to a complete sharing of energy before the nucleon is ejected.

- Characteristics:

- The direct reactions involve a single-nucleon interaction and are fast. In contrast, compound nucleus reaction involve many nucleon-nucleon interactions, in fact very many so these collisions lead to a complete thermal equilibrium (equal energy partition between nucleons) inside the compound nucleus.

- Since energy equilibration require time, the compound nucleus reaction are significantly slower than direct reactions.

-

The compound system releases energy by emission of neutrons, protons, $\alpha$ particles and $\gamma$-rays, but has a lifetime on the order of $10^{-19} s$. This time may seem short but it is $~$ 1000 times longer than the characteristic time for direct reactions.

- The compound nucleus is formed when the projectile and target nuclei merge, and the nucleon is ejected after the compound nucleus has had time to equilibrate. Video below shows an example of the compound nucleus mechanism.

- Transfer Reactions

- Involve the transfer of one or two nucleons between the projectile and the target.

- Example: A deuteron incoming and turning into a proton or neutron, adding a nucleon to the target X to form Y.

- Resonance Reactions

- In these reactions, the incoming particle forms a quasibound state before the outgoing particle is ejected.

Assignments

Identify the type of reaction:

-

$ n + \ce{^235U} \to \ce{^236U^*} \to \ce{^92Kr} + \ce{^141Ba} + 3n $

-

$ n + \ce{^10B} \to \ce{^11B} + \gamma $

-

$ n + \ce{^10B} \to \ce{^11B} + \gamma $

-

$ d + \ce{^14N} \to p + \ce{^15N} $

-

$ p + \ce{^15N} \to \ce{^16O^*} \to \alpha + \ce{^{12}C} $

Compound-Nucleus Reactions

- When an incident particle enters a target nucleus with an impact parameter smaller than the nuclear radius, it interacts with one of the nucleons, possibly through scattering.

- The recoiling nucleon and incident particle lose energy in successive collisions.

- The energy is distributed among the nucleons, with a small probability for a nucleon to gain enough energy to escape, akin to molecules evaporating from a hot liquid.

Symbolic Representation

The reaction can be written as:

\(a + X \to C^* \to Y + b\)

where \(C^*\) is the compound nucleus. In compact form, the reaction is represented as:

\(X(a,b)Y\)

- Two-Step Process:

- Formation of the compound nucleus.

- Subsequent decay of the compound nucleus.

- Key Assumption:

The relative probability for decay into specific final products is independent of the formation process.- Decay probability depends only on the total energy, governed by statistical rules.

Example

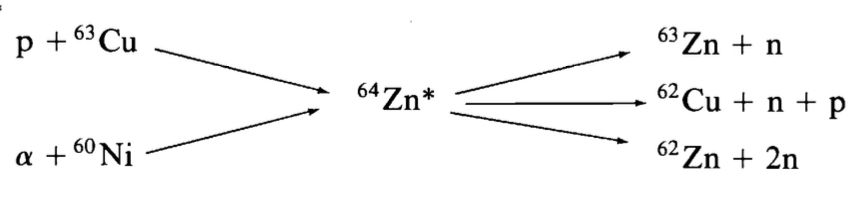

- The compound nucleus \(^{64}\text{Zn}^*\) can be formed by:

- \[p + ^{63}\text{Cu}\]

- \[\alpha + ^{60}\text{Ni}\]

- Possible decay pathways include:

- \[^{63}\text{Zn} + n\]

- \[^{62}\text{Zn} + 2n\]

- \[^{62}\text{Cu} + p + n\]

- Cross-section comparison:

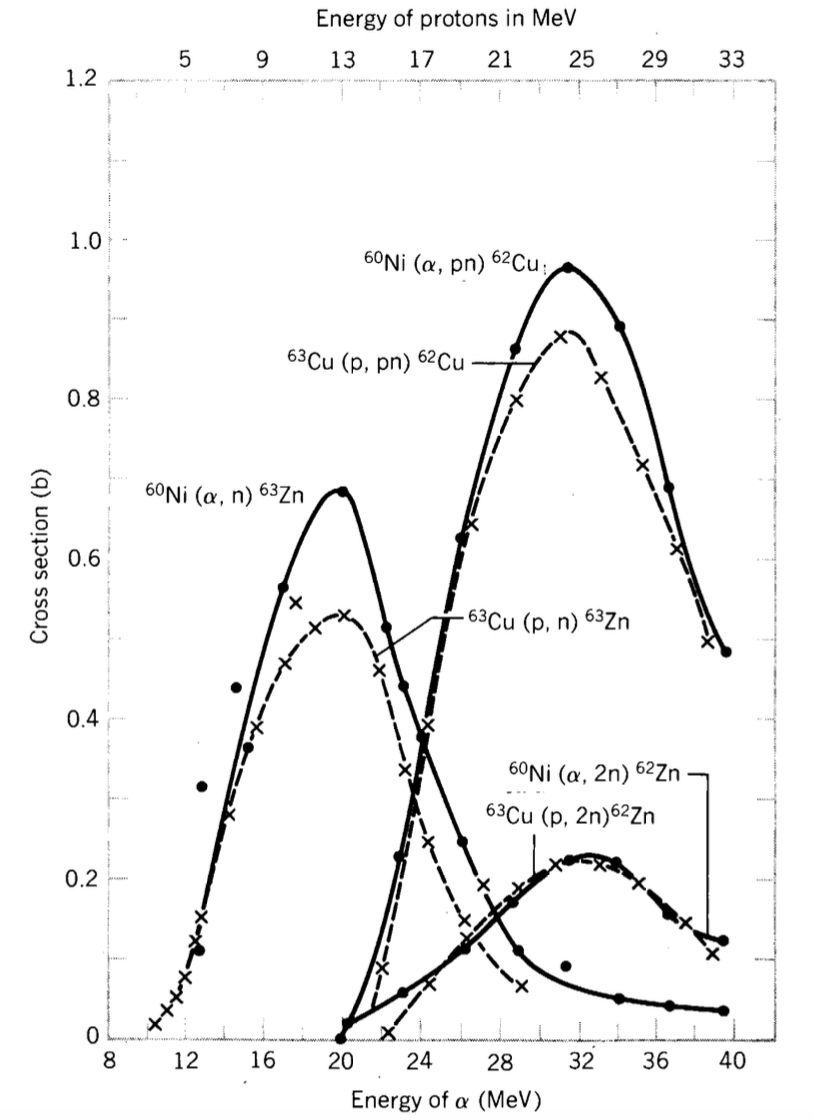

If the model holds, reactions like \(^{63}\text{Cu}(p,n)^{63}\text{Zn}\) and \(^{60}\text{Ni}(\alpha,n)^{63}\text{Zn}\) have similar relative cross-sections at incident energies providing the same excitation energy to \(^{64}\text{Zn}^*\).- Observation: Experimental data (Figure-1) supports this model, showing agreement across cross-sections.

Figure-1:Experimental cross sections for $(p,n)$, $(p, 2n)$, $(p, pn)$ reactions on $Cu^{63}$ and for $(\alpha, n)$, $(n, 2n)$, $(\alpha, pn)$ reactions on $Ni^{60}$ are plotted against $E_{p}$ and $E_{\alpha}$, respectively. The scale of $E_{p}$ has been shifted by 7 MeV with respect to the scale of $E_{\alpha}$. Source: S. N. Goshal, Phys. Rev. 80, 939 (1950).

Conditions for the Model and Characteristics

- Works best at low incident energies (\(10-20\ \text{MeV}\)) where the projectile is unlikely to escape intact.

- Suitable for medium-weight and heavy nuclei, where the nucleus can absorb the incident energy.

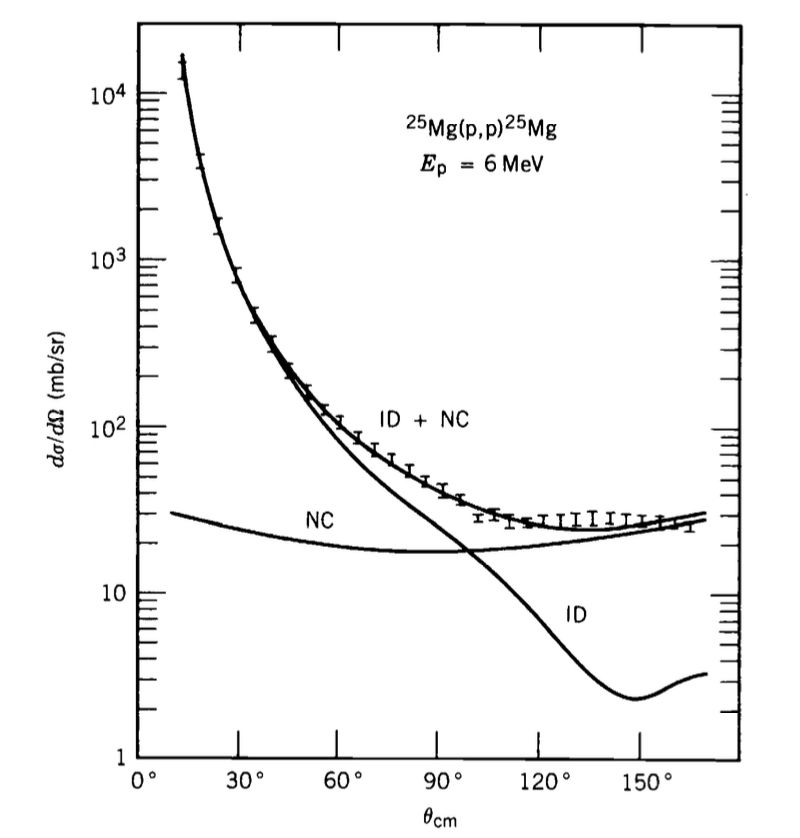

Angular Distribution

- Due to random nucleon interactions, emitted particles generally exhibit isotropic angular distribution.

- Exception: For heavy ions with significant angular momentum transfer, particles may emit preferentially at \(0^\circ\) and \(180^\circ\).

Figure-2: The curve marked NC shows the contribution from compound-nucleus formation to the cross-section of the reaction: $^{25}\text{Mg}(p,p)^{25}\text{Mg}.$ The curve marked ID shows the contribution from direct reactions. The direct part exhibits a strong angular dependence, while the compound-nucleus part shows little angular dependence. Source: A. Gallmann et al., Nucl. Phys. 88, 654 (1966).

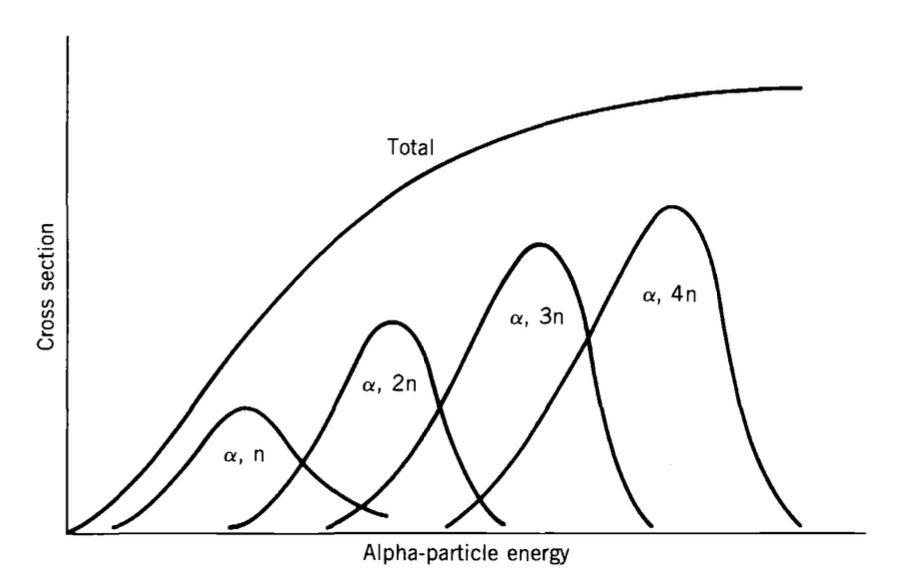

Energy Dependence

- The “evaporation” analogy holds:

- Higher energy leads to more particle emissions.

- Cross-section for reactions \((a,xn)\) shows Gaussian-like behavior:

- Increases to a maximum.

- Decreases as higher energy promotes additional particle emissions.

Figure-3: At higher incident energies, it is more likely that additional neu-trons will “evaporate” from the compound nucleus.